Methodological Behaviourism: A Tale of Pavlov’s Legacy in the Modern World

On a crisp autumn morning, a group of eager psychology students gathered in a lecture hall at the University of Edinburgh. At the front stood Dr. Margaret Ellison, a renowned psychologist with a passion for storytelling as a tool for education. Today’s lecture wasn’t just about dry theories; it was about methodological behaviourism—a framework that would revolutionise their understanding of human behaviour.

Margaret began with a tale. “Imagine a young boy named Jamie,” she said. “Jamie lives in a small seaside town, where his parents run a bakery. Every morning, they call him to breakfast with the cheerful clang of a bell—a family tradition dating back generations. But Jamie’s story isn’t about warm croissants or golden sunsets; it’s about how human behaviour can be systematically observed and understood without delving into subjective mental states.”

Jamie’s Bell: A Modern Pavlovian Journey

Jamie’s Bell: A Modern Pavlovian Journey

Unbeknownst to Jamie, he was a walking experiment inspired by Ivan Pavlov’s classical conditioning. Over time, the sound of the breakfast bell became more than just a signal for fresh bread and jam; it became a conditioned stimulus. Jamie would feel hungry every time he heard the bell, whether or not breakfast was ready.

Dr. Ellison smiled as she paced the room. “This, my dear students, is behaviourism at its core. And while Pavlov’s dogs are where we often start, methodological behaviourism takes a step further.”

What Is Methodological Behaviourism?

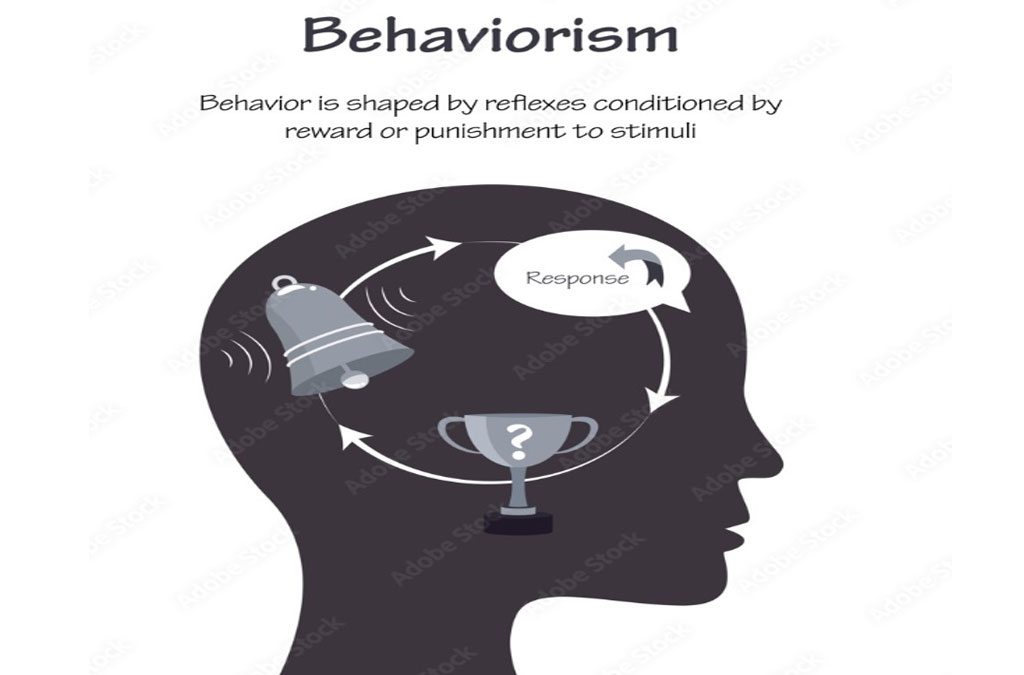

Margaret continued. “Methodological behaviourism builds upon classical conditioning, asserting that psychology should focus on observable behaviours—actions, responses, stimuli—not the unobservable mental events lurking behind them.”

It was an idea pioneered by John B. Watson, who argued that introspection and speculation about thoughts and feelings were subjective at best, and unscientific at worst. By isolating behaviour from mind, methodological behaviourists sought to understand and predict human actions in a systematic, scientific way.

“But what of Jamie? Is he more than a Pavlovian product? Can we delve into his thoughts and emotions?” Margaret posed the question with dramatic flair. “Methodological behaviourism doesn’t say those elements don’t exist; rather, it insists they cannot be objectively measured. Only what we can observe should guide our understanding.”

The Baker’s Experiment: Applying Behaviourism

In Jamie’s world, the bakery wasn’t just a place for indulgence—it became a laboratory for behaviourism. His parents noticed that the bell sound alone wasn’t always enough to bring him to breakfast promptly. So they introduced a new element: praise for arriving on time. This was operant conditioning, pioneered by B.F. Skinner, another behaviourist who focused on the consequences of actions as reinforcements or punishments.

Jamie’s swift arrival meant warm praise, and sometimes even a sweet biscuit. Soon enough, the bell sound paired with positive reinforcement made breakfast a perfectly timed ritual.

Criticism and Adaptation

As Margaret guided her students back to the theoretical underpinnings, she addressed the criticisms of behaviourism. “Now, it’s important to note,” she began, “methodological behaviourism has its detractors. By dismissing unobservable mental states, critics argue it oversimplifies the human condition. Thoughts, emotions, and consciousness—can we truly ignore them?”

Yet behaviourists themselves evolved in response. Methodological behaviourism paved the way for radical behaviourism, which included private events, such as thoughts and feelings, within the scope of analysis, though these remained linked to observable behaviours.

A Contemporary Lens

As the lecture drew to a close, Margaret brought Jamie’s tale into the modern age. “Today, methodological behaviourism plays a critical role in fields like education, therapy, and even artificial intelligence. Think about every time you’re nudged by an app notification or rewarded with a digital badge for completing a task. Pavlov’s legacy, Watson’s theories, Skinner’s principles—they’re all alive and well in the world around us.”

Jamie may have grown up and left his seaside town, but the bakery bell still rang true in shaping his daily routines. And for the students of Edinburgh, his story was a vivid reminder of how the principles of methodological behaviourism transcend the confines of academia, weaving their way into the fabric of modern society.

Final Note: Dr. Margaret Ellison closed with a thoughtful challenge: “Observe the world around you, and think about how behaviour is shaped—not by what lies hidden within the mind, but by what’s observable, measurable, and most of all, repeatable. That’s the legacy of methodological behaviourism.”